Rethinking the Building Block

Toy companies Roominate and Crossbeams, both founded by Caltech alumni, challenge traditional ideas of what a toy is, whom it’s made for, and how it can inspire.

Sydney Fish, age 9, takes a break from the morning session at her summer camp to build a toy house. Using an arrangement of brightly colored pieces, she assembles the living room: chairs, a table, and a tiny sofa. Then, she does something more—she wires a portion with electricity.

“I just made a fan,” Sydney says, flipping a switch. A small, battery-powered propeller spins to life, which Sydney makes sure to explain. “I took this circuit and connected it to the motor. Then these two wires are connected to the battery.”

This isn’t your typical doll house. Sydney is playing with Roominate Chateau, a building toy marketed primarily to girls, designed to foster an interest in science, technology, engineering, and math—or STEM skills. The San Francisco-based company was founded by Bettina Chen (BS ’10) and Alice Brooks, who bonded while in graduate school together at Stanford. “We were among a handful of women with engineering degrees,” Chen recalls. “We thought, ‘Why aren’t there more women like us? And what can we do to change that?'” Chen traced her own interest in science to the toys she used as a child: building toys like Lego blocks and Tinkertoys.

Building sets have been used for centuries to drive curiosity and teach spatial relationships. Today, they’re also big business. According to the Toy Industry Association, in 2014 the segment made up 10 percent of the overall toy market and generated $1.85 billion in sales. That’s a lot of blocks. Yet most are explicitly marketed to boys. Of the nearly 2,000 building sets on the Toys R Us website, nearly all—92 percent—are labeled as appropriate or intended for boys, while only 56 percent are similarly categorized for girls.

“There’s a big gender gap,” Chen says. “Most traditional ‘girls toys’ don’t offer play that develops spatial and problem-solving skills, which research has shown lead to greater interest in STEM fields,” she says. Indeed, one study, published in 2001 in the Journal of Research in Childhood Education, found that kids who played with building sets scored higher on standardized math tests.

Chen and Brooks designed Roominate to address that. Children can build houses using batteries and simple motors to include electric fans, elevators, even washing machines. Since its launch in 2012, Roominate has garnered a great deal of press. The young founders raised more than $85,000 on the crowd-funding site Kickstarter, then, last fall, they secured $500,000 in additional funding on the TV show Shark Tank. Forbes declared Roominate one of the “top 10 toys that kindle creativity.”

Michael Doane, an instructor at Sydney’s camp—iD Tech Mini, a San Francisco Bay area-based summer STEM program that specializes in teaching kids technology skills, including programming, video-game design, and robotics—says the effects of building toys like Chen’s Roominate are noticeable. “[They] allow children to think abstractly,” he says. “That impacts their interest and attention when they return to a project.”

Chen isn’t the only Caltech graduate to become enamored with building sets.

In Colorado Springs, Charles (BS ’95) and Monica Sharman (BS ’95) realized that there were other potentially underserved groups—teenagers and preteens. “Most building sets are thought of as ‘kids toys’ and are sold to children under 11,” says Charles, who is an electrical engineer by trade. “After that, there’s a shift from actively creating with toys to passively consuming.”

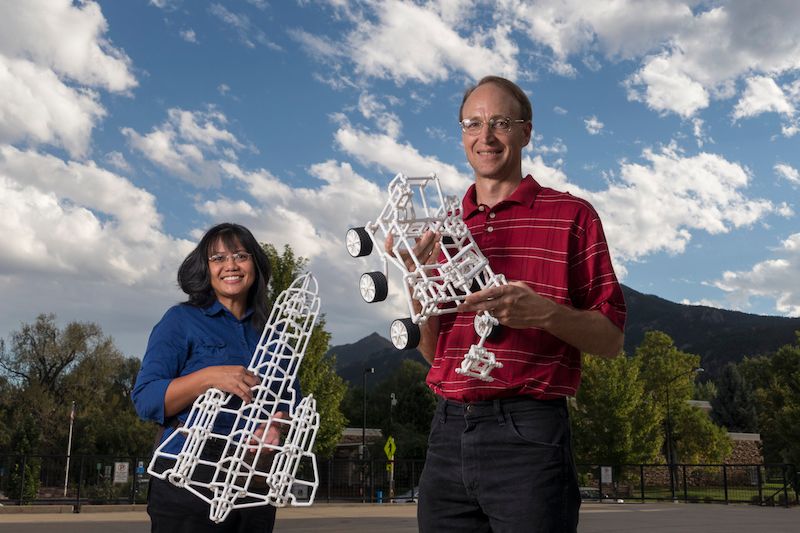

Monica (BS ’95) and Charles Sharman (BS ’95) with models built using Crossbeams.Photo: Glenn Asakwa

The Sharmans, who began dating while at Caltech and married soon after graduation, launched Crossbeams in 2014, a toy designed for more advanced construction than typical play sets. The pieces, simple white tubes that come in a variety of shapes, can combine in surprisingly sophisticated ways to form models of motorcycles, planes, even a seven-foot-tall Saturn rocket. They’re also strong: twist-lock connections allow models to withstand more than 20 pounds of force. Crossbeams has caught the attention of toy enthusiasts and was recently featured in the tech magazine Gizmag.

The Sharmans see Crossbeams as a link between starter building sets and advanced engineering. “It works as both a toy and as a platform for mechanical prototyping,” Charles says. “We want to keep children creating. After all, engineers play, too—it’s just that our toys are bigger.”

How effective can toys like this be at developing an interest in science? Time will tell, but back at the camp, Sydney offers an encouraging clue. Putting the finishing touches on her Roominate house, she smiles and says, “I want to be an engineer.”

by Lori Dajose (BS ’15)

Related Articles

-

Support the Caltech and JPL Disaster Relief Fund

Support the Caltech and JPL communities impacted by Southern California's devastating fires.

-

Resources and Response for the Caltech Community from President Thomas F. Rosenbaum

A message on resources and response for the Caltech community from Thomas F. Rosenbaum, Sonja and William Davidow Presidential Chair and Professor ...

-

A Message to the Caltech Community from President Thomas F. Rosenbaum

President Rosenbaum addresses the impact of the Eaton, Palisades, and Hurst fires on our community and shares resources to support those affected.