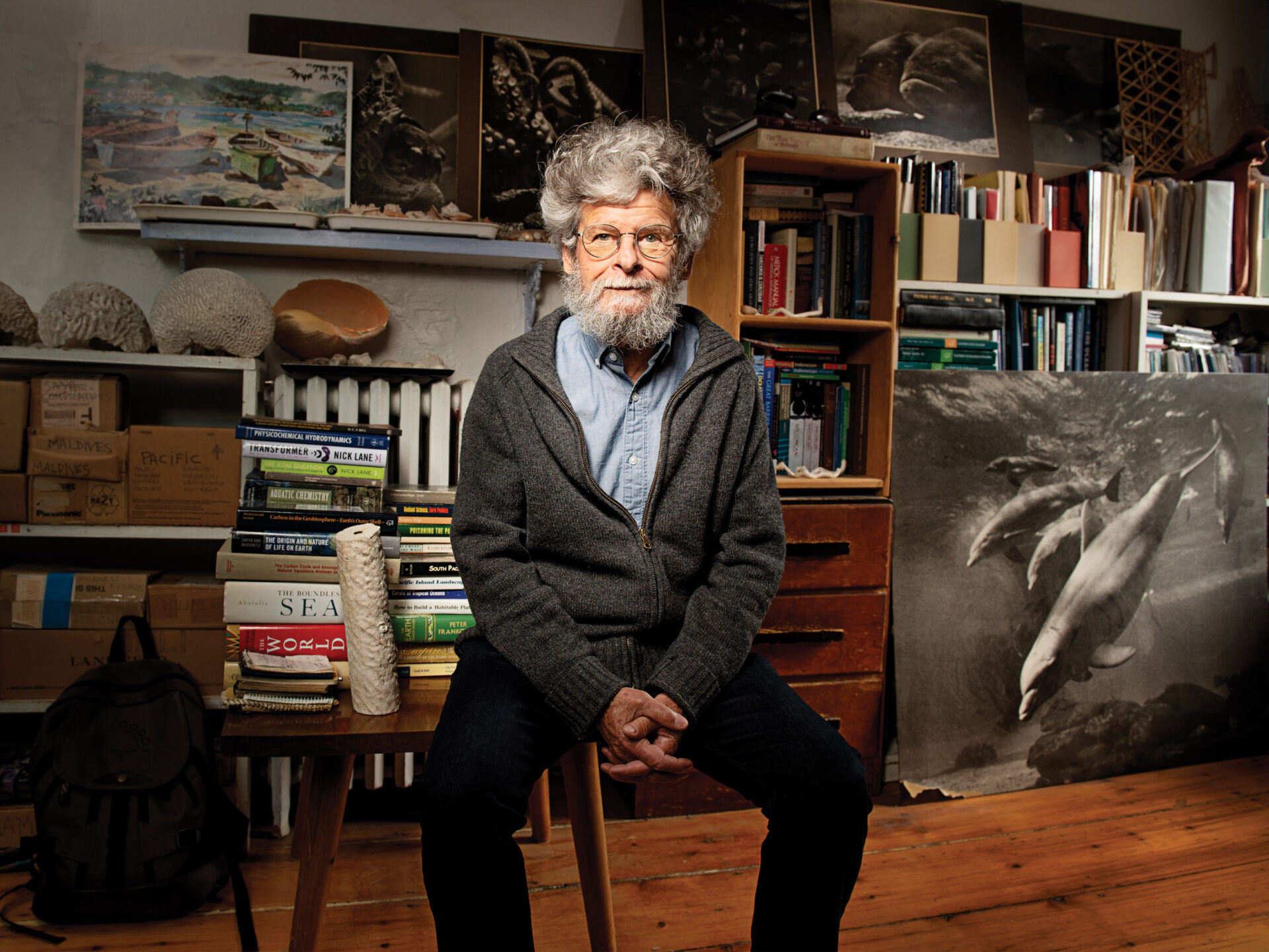

Tom Goreau, PhD (MS ’72) is a trauma surgeon for the ocean. Since the late 1980s, Goreau and his colleagues have installed more than 700 electric reefs to protect delicate coral ecosystems renowned for their biodiversity and beauty—and increasingly stressed and weakened by climate change. Between 1957 and 2007, over half of the coral reefs in the world died, according to research published in 2021. And, if global temperatures rise further, scientists predict that all of them will be wiped out.

“We can help put coral reefs on life support,” Goreau says, “but the problem won’t go away until global warming itself disappears. That’s the issue.”

Oceans shield us from the harshest effects of climate change. They absorb greenhouse gasses and heat from the atmosphere and convert them into life-giving oxygen or store them deep in the sea. This process comes at a cost to the ocean’s chemistry: Seawaters are warmer and more acidic. While some plants and animals will survive in these harsher conditions, many others, including corals, will not. These fragile creatures face other dangers, too, including sewage runoff, coral diseases, and overfishing, which make their survival even more challenging.

Goreau’s answer to this critical threat is Biorock, an invention that is as ingenious as it is simple. Steel rods, configured into various formations— domes, rings, and slopes—are tethered to seabeds. Once in place, power sources, often from solar panels floating above on boats, generate low-voltage electricity. Weak electrical currents cause minerals to grow and cover the steel with limestone rock that is two to three times harder than concrete. Coral fragments attached to the electric reef grow faster and survive high temperatures, giving them a new chance to flourish and propagate.

Today, Biorock reefs are in more than 40 countries in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Coral reefs that once were bleached and barren have regained their vibrant hues and now offer food and shelter for an array of marine life. Like natural coral reefs, Biorock systems also promote biodiversity and fisheries, while reducing wave energy to help prevent flooding and beach erosion.

Goreau was inspired to create Biorock by the late Wolf Hilbertz. The architect sought to eliminate building materials that had large carbon footprints, such as Portland cement and concrete, by growing solid structures in the sea. He imagined underwater factories producing walls, roofs, and foundations from limestone. The green building concept never gained traction, but Goreau invited Hilbertz to work together on coral reef regeneration.

“We can regenerate an ecosystem full of fish and grow a beach back at a fraction of the cost.”

Goreau soon learned that inventing solutions was the easiest part of rehabilitating coral reefs. Installing electrified reefs on public property involves bureaucratic maneuvering, funding, and persistence. In response, Goreau established the Global Coral Reef Alliance in 1990, which empowers indigenous peoples to identify how to address climate change in their communities, learn how to build Biorock artificial reefs, and advocate for regeneration of coastal ecosystems. Some of Goreau’s success stories are in Indonesia and the Maldives, whose economies rely on fishing and tourism. As coral reefs vanished, fish populations dwindled and beaches had retreated so much that buildings and trees were falling into the sea. Goreau and locals reversed that trend in months. “People spend millions of dollars dumping sand on beaches, only for them to wash away at the end of the tourist season,” Goreau says. “We can regenerate an ecosystem full of fish and grow a beach back at a fraction of the cost.”

Sharing the beauty and function of coral reefs is a Goreau family profession. His late grandfather, Fritz Goro (who changed his surname after fleeing Nazi Germany), was one of the most acclaimed science photographers of the 20th century. During his four-decade career with Life magazine, Goro photographed Bikini Atoll and all 1,429 miles of the Great Barrier Reef. Using new techniques such as macro and underwater photography, Goro shared the captivating beauty and intricate details of coral reefs with millions of readers.

Goreau’s father, Thomas Fritz Goreau, discovered coral biology as a graduate student working on the Bikini Scientific Survey. While Goro snapped photos for the military, the young researcher collected samples of marine life before and after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Bikini Atoll. After earning his doctorate at Yale, Goreau and his wife, Nora Goreau, the first Panamanian marine scientist, moved to Jamaica. Surrounded by stunning coral reefs, they founded a research lab.

“My father knew more about coral reefs than anyone who has ever lived … I had to continue his efforts and tell people what was happening to them and why.”

At 6 years old, Goreau joined his father on coral diving expeditions. Yet, when the time came to pick a college major, Goreau looked up to the stars. He studied planetary physics at MIT, planetary astronomy at Caltech, and biogeochemistry at Harvard. His career plans in astronomy changed when his father died at 45 from cancer caused by nuclear radiation exposure at Bikini Atoll. He left behind a trove of uncompleted research, unanalyzed data, and a rich library of coral reef images. Goreau refused to abandon his father’s unfinished work.

“My father knew more about coral reefs than anyone who has ever lived,” Goreau says. “I had to continue his efforts and tell people what was happening to them and why.”

Following in his family’s footsteps has been a mixed blessing. He shares his family’s appreciation of coral reefs with new generations, as well as their commitment to understanding and repairing them. But Goreau has found the world is largely indifferent to these insights. Many of his projects languish for decades due to a lack of financial and government support.

Only now are funders approaching Goreau and the alliance. With additional support, Goreau can pursue large-scale projects for maximum impact, such as protecting atolls from global sea-level rise. “Coral reefs, low islands, and coasts may disappear entirely if we don’t act,” he says. “I just hope it’s not too late.”