Life in Transition

As she steps down as CEO of the Anita Borg Institute, Telle Whitney (PhD ’85) reflects on her career in tech—and the path ahead for the next generation of women.

by Maureen Harmon

Photo by Melissa Golden

At the end of September, Telle Whitney (PhD ’85), CEO of the Anita Borg Institute, stepped down to make way for the next chapter of her life and a new CEO for the Institute. From Caltech to researcher to entrepreneur to advocate for women in technology, her career has thrived on risk-taking and transition—and she’s inspired and assisted hundreds of thousands of women along the way. Since founding the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing with Anita Borg in 1994, the annual event has grown from 500 people to well over 18,000 this year. (This year’s celebration sold out in five hours.) Here, Whitney looks back at a successful career as a woman in the male-dominated world of technology, or as she would prefer, a successful career. Period.

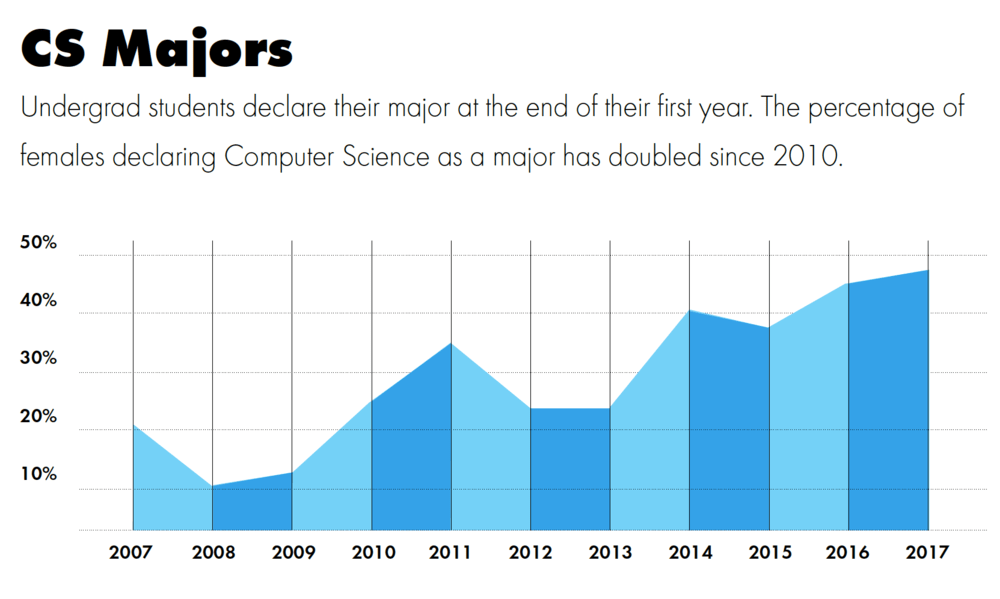

Computer Science is the most popular major for women on campus. In fact, there are more women declaring as CS majors than there are total majors (male and female) in any other subject on campus.

How did you first become interested in technology?

I grew up not even considering technology as a career. In fact, I went to the University of Utah for my undergraduate degree. I started in theater and almost dropped out. Then, because I was desperate, I took what they call an “Interest Inventory Test,” which matched my interests with interests of people in various fields. Computer programming came up above everything else.

You started your career as a researcher at the Schlumberger Palo Alto Research Center working on semiconductors and building chips before moving on to technology start-ups. What was it like to be a woman working in Silicon Valley in the ’80s?

There weren’t a lot of women around in the ’80s when I began my career, but like many women, I wanted to be recognized for my work. I did not want to be viewed as “a woman in technology”—I was just a technologist. But I did develop a network of women technologists who were very supportive in those early days. In fact, when I first moved here in 1986, I met Anita Borg. Anita was a very close friend of mine. Although we worked at very different places with very different interests, we were supportive of each other in the nearly all-male world in which we were working.

When it comes to women in technology, what are the differences you’re seeing in the field today?

I work with literally hundreds of companies that work to bring more women into technology, so there’s a lot more interest than there was before. Even though the percentage of women in technology hasn’t necessarily gone up dramatically, the sheer volume of women—the numbers—have gone up significantly in the industry. There are a lot more women in the field today and much more interest—especially in the larger companies—to recruit, retain, and advance women technologists. It’s a much more common conversation today than it was when I was young in my field.

Having said that, the startup culture can be very challenging, and sometimes, inappropriate, for women. There are some bad behaviors that we have seen in the media and that have been shared by brave and courageous women that really have been rather horrifying. These are the things that have been going on for years, that have been under the radar that people have not been talking about. Looking at the future, we’ve got to be able to surface these conversations and support those who speak out, or we’re never going to create change.

The Anita Borg Institute was founded on the belief that women are vital to building technology that the world needs. They work with companies to recruit, retain, and advance women in technology. Can you cite any specific examples of programs that you think are particularly successful and innovative? There’s a couple of companies that do this well. One is Intel [cofounded by Gordon Moore PhD ’54]. Intel has really embraced this issue deeply. It’s not so much the individual program, it’s the collection of the approach that really matters. One of the important aspects is support from the top.

The other aspect is how these companies measure change. Intel really looks at the numbers and where they’re losing people. Then they deploy programs that are targeted to look at those particular areas. From our Top Company program, we see that there are three programs included in companies that have more women. The first is flexible work schedules. The second is leadership training, which is really important in order to understand your population and have targeted training for both women and minorities to help them move up. The third is diversity training. Intel has all three of those, and they track them regularly, and release their findings twice a year, measuring progress at every step.

What are your hopes for women in the computer science field a decade, or two decades, from now?

Technology really is going to be the deciding factor in what influences our lives 50 years from now, 100 years from now. My hope for the future is that women are increasingly part of that conversation. Not just about what technology we want to create, but also in creating it.

You want your smartest people at the table. You want to have the smartest people you can creating the things that are impacting our lives. It doesn’t make any sense to be exclusive of 50 percent of the population. You’ve got to believe that within that 50 percent of the population, there are future geniuses.

As women in tech climb the corporate ladder, what keeps them climbing, and what obstacles face women who are now sitting in executive seats?

A lot of it is about corporate culture. If women felt like they belonged, they would stay. The single most commonly articulated reason for why women leave is that they don’t know about advancement. You see a lot of leadership that talks about things like hours and childcare being the reasons why women leave, but that’s not what the social science says. Women are as ambitious as their male counterparts. They just have more commitments, and they don’t understand how to advance within this culture.

One obstacle is that men tend to promote people who look like them, so women don’t get the promotions. There’s a lot of feedback right now about the performance review bias. If you do an analysis of performance reviews, you see certain words used over again. Men talk about “ambition” and “hard-charging personas.” But those tend to be male characteristics, and those are seen as key characteristics for moving up in an organization. Women who are ambitious and aggressive often get dinged on likability.

What advice do you have for women leaders?

Stay focused on key outcomes, but also remember that women who are in senior positions are important role models for all women in an organization. You need to take that responsibility seriously, be available, and speak broadly. Just recognize that whether you like it or not, you are a role model for everybody in that company.

What do you think companies in our country are doing right to address the gender imbalance in computer science and in STEM fields, and what could we be doing better?

My key point to companies is that it’s not a pipeline issue. I do know that most people believe it’s a pipeline issue, but if you don’t change the organizations that are hiring these women, then you can change the pipeline from now until you’re blue in the face, but the women won’t want to stay. It’s very easy for companies to focus on the pipeline without looking internally about what they need to do culturally. Hold your leaders accountable. Look at your culture. What you measure, you will change. Understand and create an inclusive culture from which you can learn.

LEADING BY EXAMPLE — This past October, 40 current students attended the Grace Hopper Celebration in Florida. They met Telle Whitney (pictured here in the purple jacket) and shared their Caltech pride.

“We intentionally make it our goal to positively change the reputation and global perception of an African technologist.”

– Kudah Mushambi, Co-Founder of Adaire

The realization was well timed. Mushambi was at a career crossroads, and his former boss at Google, Andreas Henning, had just moved back to his native Germany. After mulling over the issue with his wife and Henning, he landed on a solution: Africa. It has the youngest and fastest-growing population of any continent, and Mushambi, who was born in London and raised in Zimbabwe, knew it had a vast reserve of untapped tech talent.

That opportunity is at the heart of Adaire, which Mushambi and Henning cofounded in 2021. “DACH is in the middle of a war for technology talent,” Mushambi says, noting that the company’s competitors are based in what he calls more traditional software-outsourcing hubs, like India, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. “Right now, the African talent is invisible, at least on the global stage,” Mushambi notes. The continent is ignored by boardrooms globally, he says; even some African companies would rather engage an Indian firm.

But Africa, he says, “has eager, youthful, dormant, and underutilized talent, keen to access new opportunities.”

Fittingly, the name Adaire is inspired by a Namibian phrase, “Ada I re,” which means, “Let’s go.” And Mushambi is ready.

What do you consider the most transformative moments in your career, and how did they prepare you for what you are doing today?

If I look back on my career, it really was about taking risks. Every step of the way, as I became aware of what I wanted to do, I just went for it. And I really wasn’t sure it was going to succeed. When I joined the Anita Borg Institute, which at the time was called the Institute for Women in Technology, most of the board felt like the Institute wasn’t going to survive. I was encouraged to take risks.

My career has also been about perseverance. There weren’t a lot of hiding places along the way, and I continued to show up every day, figure out what to do next, and decide how I could make my work better. I’ve also had to be true to who I am. We’ve got to listen to our inner core. It’s what guides me every day, when I remember to listen to it, though sometimes I forget.

My career has also been about transition. This year, I’m stepping down as CEO of the Anita Borg Institute. Transitions are my life right now.

One of the legacies you’re leaving behind is the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing. Can you tell us about the impetus for that?

Anita and I discussed having a conference where it wasn’t just about discussing the issues regarding women in technology but about celebrating their work. We sat down in a coffee shop in downtown Palo Alto, and we looked at each other and neither one of us really had any idea how to start a conference. We just decided to start one.

For the first conference, we invited the top women in the field at that time to speak, and they all said yes. As an aside, the Turing Award is the Nobel Prize for the computing community. In the history of the Turing award, there’s only been three women to date who have received it. All three of those women were scheduled to speak at that first Grace Hopper Celebration.

What was it like when it actually came to fruition?

This was several years in the making. There was a moment when we were at the hotel on the balcony, looking out over the reception areas. The whole corridor was swarming with women, and it was inspiring. I remember thinking, This is my time. This is where I belong. For people who come to the Grace Hopper Celebration today, it’s a stunner. You cannot imagine what it’s like to be at a technical conference just surrounded completely by women. It’s life-changing.