Animating Forces

These Caltech alumni help create the animated films that captivate our imaginations.

by Erin Peterson

Illustrations by Michael Kirkham

Great animated films do more than just delight and entertain us. Done well, they can reveal emotional truths in ways that even real life can’t.

Getting to these powerful moments requires careful attention to every detail, since even the tiniest flaws can distract an audience. Through their work with some of the very best animation studios, Caltech alumni have played essential roles in bringing many of the most beloved animated movies to life. They’ve worked on blockbusters that include Inside Out, Moana, Zootopia, and Kung Fu Panda.

Here, they share with us some of the insider secrets that they’ve used to make characters more lovable, scenes more realistic, and every moment a little more wonder-filled.

Harnessing Moana’s Liquid Assets

In his work on films such as Frozen, Zootopia, Tangled, and Big Hero 6, Jason MacLeod (BS ’93) tackled plenty of interesting challenges as one of Disney Animation’s lighting and compositing artists.

But his work on the sparkling turquoise waters of Moana offered up some uniquely difficult tests of his—and his teammates’—skills. For example, creating a wave breaking on the sand consists of countless tiny elements of timing and physics. The effects team used a wave model developed by the U.S. Army’s Coastal Engineering Research Center to simulate the shallow water in the coves. To add additional detail, they also used a technique known as “level set compositing” to blend the areas where open water transitioned to waves peeling, crumbling, and breaking at the shore.

“My personal work was on the lighting side – more about the color—and the wave and water simulation work was done by the effects team.” Says MacLeod.

Water, it turns out, is one of animation’s very toughest challenges. “There aren’t too many shortcuts with water, because it’s so complex,” MacLeod says. “You can see through it. Light reflects off of it and refracts through it. In larger amounts, it takes on a color. It has waves and surface tension.”

To get every moment just right, MacLeod and his colleagues spent plenty of time trying to capture the nature of the planet’s most abundant liquid. Some traveled to the Polynesian islands of Fiji and Tahiti. MacLeod headed to Malibu, where he studied how the sun reflected off the water, what the horizon looked like on both sunny and cloudy days, and how water and sand interacted and shifted when waves broke against the shore.

And while he and his teammates took their share of photos and videos during the research phase of the project, one of their primary tools was paint. “Sometimes, pictures don’t capture the truth of the feeling that you had while you were somewhere. Painting helps you sell an emotion, because you can simplify some things and play up others,” he says. Animation uses many of painting’s techniques to convey emotions: artists typically increase color saturation for celebrations and happy scenes, and use lots of gray and washed out colors for sad scenes.

For MacLeod, much of the joy of his work comes when he’s able to pull together all of his research to solve a particularly knotty problem. “I think about work like a detective: I’m putting stuff on the bulletin board, and by the end, all the clues will point to so-and-so. But I could never have known it until I did all of the work.”

Perfecting Po in Kung Fu Panda

Po, the goofy hero in the Kung Fu Panda franchise, once seemed like an impossibility.

It wasn’t his personality. It was his tricky anatomy. Po’s chubby belly and short, thick neck presented all sorts of problems for Peter Farson (BS ’81), a lead character technical director at DreamWorks Animation.

Farson, whose credits include The Boss Baby, How to Train Your Dragon, and Shrek, explains that developing the Jack Black–voiced character demanded patent-worthy advances. Farson’s specialty is in an area known as “body deformation.”

Creating a character like Po starts with work in the modeling department, with relatively simple structures. From there, it heads over to Farson, and he and his team take the characters to a new level. “We define where the skeleton should be placed to help everything—head, torso, fingers, toes—move just the right way,” he explains. Next, they attach “skin” that conforms to that skeleton. From there, the work is passed off to the animation department, who will perform the acting that helps a character spring to life on screen.

While there is a certain realism required in Farson’s work, he notes that animators are always working to push the envelope. “Maybe we should be able to bend a joint 90 degrees, but animators want to go to 170 degrees. We allow them to do that,” he says.

But there are still plenty of technical challenges, even within the reality-bending world of animation. For example, when Po moved his big arms into his belly, artists needed software that would push his belly fat out of the way while creating bulges in the surrounding torso area. “We built a system for that called ‘balloon volume,’ and even got a patent for it,” Farson says. In 2009, the character was nominated for a Visual Effects Society Award.

Farson loves the chance to build technology that makes the impossible possible in animation. “It’s a combination of technical and artistic work,” he explains. “The more features you can develop, the easier you can make it for the animator to achieve the feeling of the character being alive.”

“There is no problem that can’t be solved if you figure out how to approach it, and you approach it in pieces.”

Making every move matter in How to Train Your Dragon

In a way, you can thank Gabriela Venturini (PhD ’11) for every last movement in How to Train Your Dragon—from the way that the Vikings slash their swords to the graceful flap of a dragon’s wing.

Venturini, who worked as a software engineer for DreamWorks Animation from 2014 until this past summer (she’s now at the video game publisher Activision), developed animation and rigging tools for the movie.

Because DreamWorks Animation has created its own software for its movies, software engineers like Venturini must create every bit of this made-to-order tech. (This is not the case at other major companies, which add to existing commercial software.) It’s a bit like a writer choosing to build their own version of Google Docs or Microsoft Word from scratch, she explains. “Every movement of the characters you see is created with a tool that we [developed],” she says.

Venturini’s primary focus was on rigging tools, the technology that puts the bones and skin on the character. Her team’s custom approach, though time-consuming, pays dividends for DreamWorks’ talented artists. “We are bringing artists to the table to say ‘What do you want these tools to enable you to do that you can’t do with other commercial software?’” she says. “It gives them more creative freedom and capabilities that they wouldn’t have with off-the-shelf packages.”

One of her responsibilities was to create the support systems that could zero in on a problem and help artists quickly get back on track when software didn’t do what they expected—support that was not unlike Microsoft’s old “Clippy” assistant.

While Venturini’s work gets technical fast—think interpolating curves, data structures, and complex mathematical computations—part of her job was to serve as a translator, turning artists’ visions into the software that brought their concepts to life. “Artists [and engineers] speak different languages; we often literally have different vocabularies and word meanings in our work,” she says.

When she did the work successfully, she knew she was playing an integral role for a movie that millions went on to love. “We wanted all of our artists, regardless of their technical background, to be able to be the best artists they can be.”

Making simple moments shine in Zootopia

In the billion-dollar smash Zootopia, Officer Judy Hopps is a bunny who gets the chance to solve a mysterious case. But before she becomes an amateur sleuth, she’s a humble meter maid.

In one scene, she zips around Zootopia slapping hundreds of tickets on cars parked at expired meters. You might not even notice the flashing lights on her modest cart as she speeds around the city.

But for Chris Springfield (MS ’93, PhD ’98), a lighting supervisor at Walt Disney Animation Studios, creating those lights was an intense, monthlong project. Red, orange, and blue flashers on top of the cart spin, yellow lights scroll horizontally across the back, and red and white tail lights alternate as she brakes.

Creating the complex patterns and illuminations were a programming challenge in and of itself, but Springfield’s work allowed all of the lights not just to animate but to be adjusted as needed. Other artists could change the value—the relative degree of lightness or darkness of a color—or timing to test different options. “I made sure that the tail lights looked like tail lights and that the lights [which] were traveling across the back of the cart were moving at the right speed,” Springfield says.

Though the lights appear on screen for less than a minute, they look like an amped-up version of what might be on a real meter maid’s cart, not a confusing mess of flashes and strobes. “It looks really simple, but we wanted to make sure that they were all flashing in a way that felt coherent, plausible, and real.”

Springfield’s many credits include Moana, Big Hero 6, Wreck-It Ralph, and Chicken Little. He won an Academy Award for Technical Achievement in 2002 for his role in developing Deep Canvas rendering software, which helps give paintbrush strokes a three-dimensional appearance.

Creating gorgeous clothing in Coco

In the recently released Pixar film Coco, a young Mexican boy dreams of becoming a famous musician and ends up on an unexpected adventure. Coco relies heavily on themes from the Mexican holiday Día de Los Muertos, and characters are dressed in gorgeous, detailed gowns.

It was the job of Fernando de Goes (PhD ’14) to help artists make every outfit picture-perfect—no matter how intricate. De Goes, a research scientist at Pixar, uses his deep knowledge of geometry processing to help translate an artist’s vision into a compelling on-screen creation. De Goes says he’s constantly working to develop technology that helps him open up animation possibilities in realistic ways. “Our major challenge is to direct the animation in ways that are physically plausible, but with a bit of fantasy as well.”

After collecting all the information he needed from artists—notes on the decorations and textures of the dresses, for example—de Goes developed a tool that automatically decorated the garments to the artists’ exact specifications, following every curve of the gown with precision. “The artist doesn’t have to spend their time and effort manipulating and painting the mesh [that represents the surface of the clothing],” he explains.

De Goes’s efforts allowed artists to spend more time focusing on the look of the dresses, adding more details and increasing the lavishness of every image. “Because it’s so much cheaper and easier [to do this work with the tool] artists can develop very appealing garments even for characters who are walking in the background of a scene,” he explains. “Without it, artists would never be able to add as much detail as they would like.”

In the end, de Goes wants to contribute not just to a beautiful scene, but to an overall experience. “The more realistic and rich a scene is, the more mind-blowing it will be.”

Giving emotional moments a physical presence in Inside Out

Over the past two decades, animated films have literally added a new dimension as art has shifted from painterly sketches to sophisticated 3D computer animation. That change has opened up all sorts of opportunities, but it’s also added a range of constraints.

The shape of a character—its silhouette—is one of those limitations. “In a drawing, you’ve got some artistic license. An animator might decide to smooth out or exaggerate a bump on an elbow,” explains Kurt Fleischer (PhD ’95), a senior research scientist at Pixar. “But in our computer animation system, that’s something they didn’t have as much control over.”

Using a tool that Fleischer helped develop, artists started getting back some of that freedom.

Take one recent movie Fleischer worked on, Inside Out. Because most of the characters were literally part of the mind, they didn’t need to follow nearly as many real-world rules. So, whenever a scene called for a special emotional emphasis, artists could make small tweaks to the character’s body that might not have otherwise been possible.

For example, Fleischer worked on a scene with animator Bret Parker in which the square-headed, short-fused character Anger points his finger for emphasis. Parker wanted to underline that moment by slightly enlarging the finger—a request that was too specific to accomplish with any of the available tools. Fleischer’s tool made it possible for her to make the change.

In another scene, when the Amy Poehler-voiced character of Joy hugs her favorite memory, Fleischer’s tool allowed artists to add a slight bulge to Joy’s shoulder area and cheek. “You could sense the force that she was squeezing the memory with—it’s one of the things that made that moment a little sweeter,” he says.

It’s these subtle moments, says Fleischer, that help a film hit all of its emotional marks. “Would the movie have failed without the bigger finger and the muscle bulge? Of course not. But it’s one of the 10 million things that we do to try to make the movie as powerful and expressive as possible.”

Fleischer, who has worked at Pixar for 21 years, says his focus has shifted as technology has evolved. “In the early days, it was all new—we had to invent new technology to do anything. Today, we focus on [projects that] help artists think more about the art than the technology.”

Giving Greek Gods their Power

In the 1997 Disney movie Hercules, there is a scene in which the Greek God Zeus pulls a cloud from the sky and shapes it into a tiny winged stallion: baby Pegasus. One of the people who helped make that specific magic happen was Nhi Casey (BS ’87). “I worked on a morph tool to turn clouds into objects such as columns, chairs, and animals,” she says.

Though astonishing for its time, the technology seems almost quaint to Casey now. “When I started in animation [in 1994], everything was hand-drawn and scanned into a computer,” she says. “Now, everything is computer-generated, and the complexity of the shots has gone way up.” That complexity includes realistic simulations of cloth, hair, water, and fur—all enormously difficult to get just right. It also includes a more sophisticated rendering of light, which bounces off surfaces and affects other objects in nuanced ways.

Today, she works as a software engineer at DreamWorks Animation, where she focuses on a variety of projects, including animation applications that provide live animation playback. She’s helped develop a “multi-shot feature” that allows animators not just to see the shots they’re working on, but the previous and next shots in the sequence. These features give artists a fuller sense of the context of their work.

It’s a long way from one of her first jobs, working in the lab at The Aerospace Corporation, where she did modeling of aerosol dispersion—but it was there that she first got interested in computers, and then made the leap over to animation at a time when the industry was in significant transition.

Since then, she’s worked on tools for films that included The Croods, Kung Fu Panda, and Bee Movie. And the challenges, though different, still create the same joys for her. “It’s really rewarding when we can implement a feature in a tool that allows an [animator] to do something that couldn’t be done before.”

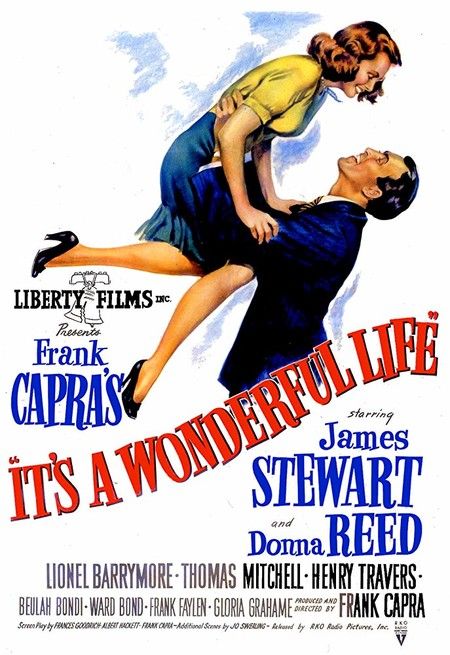

The First Star

Frank Capra (BS 1918)

Long before Techers were working to make the waves of Moana come to life, a student at the Throop College of Technology (later Caltech) was taking a rather circuitous route to the film industry. Had the family of this young man had any premonition of his future Hollywood success, they might not have asked him to abandon college for work and a steady paycheck—a much more tried and tested road for an Italian immigrant with little means. But thankfully, for this student and the whole of American culture, Frank Capra was persistent in his pursuit of the American Dream.

It was during his Throop years that Capra, who was studying chemical engineering, discovered poetry—specifically the work of Montaigne—and began to write, sparking a life of creativity. According to his biography on IMDb, Capra said: “It was a great discovery for me. I discovered language. I discovered poetry at Caltech, can you imagine that? That was a big turning point in my life. I didn’t know anything could be so beautiful.”

After earning his degree, spending time in the U.S. Army, and working as a book salesman, Capra landed a job directing a silent film at a start-up studio. That gig earned him $75 and a foot in the door of a very young film industry. Capra rose from the ground up: He worked as a property man. He cut film. He wrote titles. He spent eight years in Hollywood and New York before finally taking the director’s seat at Columbia Pictures in 1927. There he would go on to direct films like It Happened One Night, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It’s a Wonderful Life—earning six Oscar nominations and three wins for Best Director along the way.

Correction: The printed version of this story in Techer Magazine incorrectly listed Chris Springfield’s degree. He received a PhD from Caltech in ’98, not a BS.