Taming the System

How Riot Games’ Naomi McArthur keeps the peace in online gaming—and how those lessons can extend to real life

by Alexander Gelfand

Christina Gandolfo

Game designer Naomi McArthur (BS ’13) might not have a badge and a gun. But in the world of multiplayer online games, she’s the closest thing to a sheriff there is.

Outside of e-sports events, such as the 2018 LoL World Championship in Seoul (pictured here), online gamers operate in an environment in which real-world social constraints don’t exist—an environment in which they may never have to look opponents (or fellow teammates, for that matter) in the eye.

McArthur designs online behavior systems for Riot Games, the company behind League of Legends (LoL), one of the most popular video games on the planet. LoL boasted more than 80 million monthly active users in 2017 and is a pillar of e-sports, with professional gamers competing in North American, European, and Asian leagues. But some of its players can get a little salty—or worse. So McArthur and the rest of Riot’s Player Behavior Team use a combination of data science and social science to maintain order in an unruly virtual world.

LoL belongs to a class of online games that pit teams of players against each other in pitched battle. While inspiring intense loyalty, such games also breed toxicity, with the most egregious offenders spewing racist, sexist, and homophobic slurs. And LoL, a fantasy game in which two five-player teams of mages, marksmen, and other champions struggle to destroy one another’s castle-like base, is no exception, with aggrieved gamers complaining of harassment by opponents and teammates alike. It’s the kind of thing that can tarnish a game’s reputation and drive away users. (Riot has already banned several professional LoL players for in-game abuse.)

Some of this negativity, McArthur says, is fostered by the absence of normal curbs on nastiness. And some is due to the nature of the game itself.

Online gamers operate in a virtual environment where many real-world social constraints don’t exist; where anonymity and a sense that trolling is the norm mean that people spewing hate speech never have to look their victims in the eye or face the disapprobation of their peers.

“The online community is the Wild West in a lot of respects,” says McArthur, a lifelong gamer and former president of Caltech’s League of Legends Club who has faced her share of sexism online.

What’s more, weak players can drag down more competent teammates, thereby earning their enmity. “Mistakes made by a teammate can empower your rivals, who can use their newfound power to crush you,” says Bill Clark (BS ’08), an engineering manager at Riot who plays LoL under the name LtRandolph.

And because many teams are temporarily assembled by matchmaking algorithms, players rarely have to see one another again, eliminating a powerful incentive to play nicely together. Things get even hairier when players speak different languages and harbor different cultural expectations. (Riot’s European and Southeast Asian servers connect gamers from many different countries.)

McArthur and her co-workers blend quantitative techniques with social psychology to replace those missing behavioral guardrails and promote cooperation, penalizing bad behavior and rewarding good sportsmanship with A.I.-powered incentive systems.

As an online behavior systems designer for Riot Games, Naomi McArthur works to create a system of good sportsmanship in an exploding industry.

Their work makes for interesting bedfellows. McArthur, who analyzed neuroscientific data using statistical methods while studying computation and neural systems at Caltech, worked for several years with a psychologist specializing in deviant behavior, and she often collaborates with academic researchers to reap behavioral insights whose relevance extends well beyond LoL.

McArthur recently co-authored a paper with a group of researchers at MIT that used game data to investigate “collective intelligence,” or the ability of a team to perform a wide variety of tasks. Among their findings: Lasting teams perform better than temporary ones (see above re: playing nicely). So do teams with female members, who tend to be more socially perceptive than men. And the highly virtual, fast-paced nature of the game means that tacit coordination among teammates matters more than explicit communication.

These takeaways could help improve the performance of virtual teams operating in business, or even groups operating in real-world environments that share the game’s intensity and reliance on rapid decision-making—such as emergency response teams and military combat units.

McArthur herself has come to appreciate the value of such research to everyday life. “It fundamentally helps you understand the interactions you have in your day-to-day environment with your peers and family, especially when it comes to cooperative behavior,” she says.

But she’s primarily focused on applying those lessons at Riot, where she has developed machine-learning models to analyze the reports that players submit on disruptive gamers and to match that data with particular kinds of in-game activity, creating—and enforcing—a set of data-driven community standards for acceptable behavior.

The system can identify an infraction and issue feedback to offending players minutes after a game has ended, explaining precisely how they misbehaved and handing out penalties ranging from temporary suspensions to permanent bans. A new name-detection feature can even identify vulgar or offensive player names and force users to change them—a costly process that requires spending either real money or hard-earned game currency.

McArthur and her colleagues have also introduced a system called “Honor” that rewards good sportsmanship by presenting players with badges they can carry from game to game, leveraging gamers’ pride and competitiveness to encourage positive behavior. Misconduct will tarnish or break a badge, but the game’s automated systems allow players to redeem themselves, reforging their badges through good conduct and restoring their honor.

“It’s very Klingon,” McArthur says with a laugh.

It’s also effective.

“I feel encouraged to be a good player by the things that the Player Behavior Team has done,” says Clark, “and I feel like my game is less toxic than it used to be.”

To spread that love, Riot co-founded the Fair Play Alliance, a cross-industry initiative spanning more than 70 gaming companies dedicated to sharing research and best practices on ensuring fair play and reducing disruptive behavior. The goal is to make the online gaming space kinder and gentler overall, but it should pay dividends at home too.

“At the end of the day, we can clean our own yard,” says McArthur. “But if we aren’t cleaning up the entire neighborhood, people will just track things into our environment.”

Related Articles

-

Caltech Alumni Association Announces 2026 Board-Nominated Slate

We are pleased to announce the 2026 board-nominated slate for the Caltech Alumni Association Board of Directors.

-

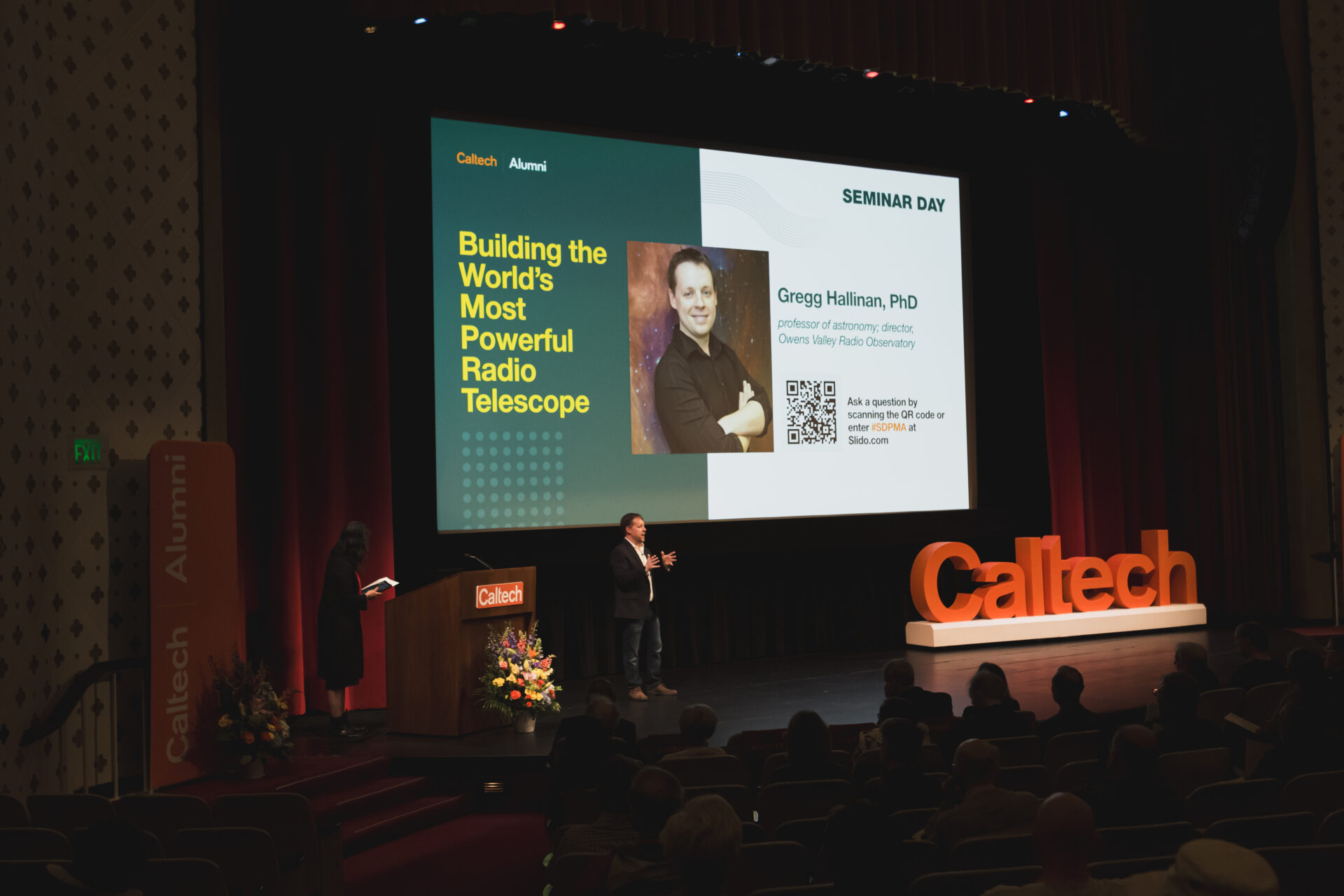

Scenes from Seminar Day 2025: Techer Families Join a Day of Discovery

View highlights from Caltech’s 88th Seminar Day with a photo gallery of campus tours, faculty lectures, student talks, and the debut of Seminar Day...

-

Support the Caltech and JPL Disaster Relief Fund

Support the Caltech and JPL communities impacted by Southern California's devastating fires.

Alexander Gelfand is a writer and recovering ethnomusicologist based in New York City. His work has appeared in the Economist, the New York Times, Wired and many other print and online publications.