The Food Lab

Harold McGee, the (somewhat reluctant) “godfather of molecular gastronomy,” talks to us about the first workshop that brought cooks and scientists together, how it came to be, and how the science of cooking became popular.

by April White

Eric Millette

Caltech Distinguished Alumnus Harold McGee (BS ’73) would like to apologize for the term “molecular gastronomy.”

“It’s pretentious,” he says of the mouthful of a phrase used throughout the 2000s to describe the newly trendy intersection of science and cooking. Coined for the First International Workshop on Molecular and Physical Gastronomy, a 1992 conference that McGee helped organize, “molecular gastronomy” unintentionally made the chemistry of cooking seem difficult, something best left to the experts. McGee, the author of On Food and Cooking, a standard required text in many culinary schools that’s also used in university science courses for non-majors, has spent his entire career telling home and restaurant cooks exactly the opposite: “Cooking is something where you apply the science with your own two hands.”

Photograph by Eric Millette

Why did science and cooking exist in isolation when you began writing about the topic in the 1970s?

There have been connections between science and the kitchen for centuries. The pressure cooker, for instance, was invented in the time of Isaac Newton. But that connection got lost in the first part of the 20th century. Scientists were focused on the industrialization of food. With the two world wars, there was an emphasis on food manufacturing and safety, rather than better ways to make a steak. And there was the development of home economics, which paid more attention to nutrition and hygiene than to pleasure and deliciousness.

What prompted the First International Workshop on Molecular and Physical Gastronomy in 1992?

It was the brainchild of a cooking teacher whose husband was a physicist. She and a colleague of his put together a meeting of scientists interested in cooking and cooks interested in science and asked me to help. It was a brand-new idea. There was a place in Italy that held scientific conferences that was happy to host it, but asked us not to call it “The Science of Cooking” because that didn’t sound serious enough. At the time, molecular biology was the scientific field with the most prestige, and gastronomy is the Greek-derived term for the knowledge and appreciation of food, so “molecular gastronomy.” I never thought the name would stick.

How did the science of cooking go mainstream in the 2000s?

It was the conflation of several unrelated things: a gradual rediscovery of its usefulness by culinary professionals, our conferences on traditional techniques, and chef Ferran Adrià’s creative efforts at El Bulli in Spain. Journalists began to attend our meetings and also saw the things that Adrià was doing with foams and gels, which relied on some understanding of their chemistry, and he got tagged with the term molecular gastronomy. He was very unhappy about that, but it helped kick-start public interest in the subject. In 2007, The New York Times asked me to write a regular column called “The Curious Cook.”

Will this renewed interest in science fundamentally change how we cook?

I think the new popularity of science in the kitchen has been a mixed blessing. Now that it is trendy to include a sentence or two about science in any food article, there’s a lot out there that isn’t reliable and a proliferation of clickbait that says, “Science says you are cooking wrong.” That’s just not the case. If you have been cooking rice a certain way all your life and it works just fine, you are doing it right. The principles of cooking haven’t changed for thousands of years, and people discovered things that work by trial and error. What science can do is help us understand why they work and implement the practical discoveries people made over the millennia in more convenient ways.

Photograph by Eric Millette

Foodies Unite

Techers in the food and beverage industry offer up dinner and drinks for the perfect night in.

Bringing Germany Home

Tyson Mao (BS ’06), co-owner of Wursthall, a German restaurant and bierhaus in San Mateo, California, serves up a recipe—courtesy of Wursthall’s chef Kenji López-Alt—for a modern take on a traditional comfort food.

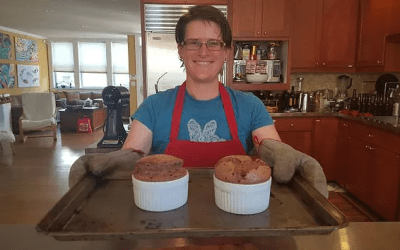

Devil’s Hoard Chocolate Soufflé

Andrew Casteel (BS ’00), founder of Laughing Monk Brewing in San Francisco, California, shares a recipe for Chocolate Soufflé made from Laughing Monk Devil’s Hoard Imperial Belgian Stout.

Delicious. Now, What to Drink?

Diego Benitez (PhD ’05), founder of Progress Brewing in South El Monte, California, knows a good meal is never complete without a complementary beverage. “I try to figure out the intricate and complicated relationship of physiological and psychological factors that determine taste preferences in people,” says Benitez, who has 10 years of professional pairing experience. Here are his thoughts on the perfect pairings for this German meal.

Berries Athenaeum

This dessert needs no introduction.

Roasted Carrot Soup

Jennifer Yu (BS ’93), the author of the popular Use Real Butter food blog, shares her recipe for roasted carrot soup. Head to her blog for more recipes, including Thai Firecraker Shrimp and Honey Sriracha Japanese Fried Chicken Karaage, where she also shares photos of her dogs and stories of her life and adventures in the Colorado Rockies.

April White is an award-winning writer, editor and researcher. She previously served as a senior editor at Smithsonian Magazine. An experienced researcher, she has also collaborated with nonfiction authors on more than a dozen book projects.